Thoughts on institutional upgrades, hierarchies versus networks, and re-wilding as an organisational design priority.

This week’s ‘Lunch with the FT’ featured the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, and he had some interesting things to say ($) about how mature democracies are taking their institutions for granted, whilst established norms of discourse are being eroded by social media:

”…I think we’re regressing . . . We developed these institutions that made us live way above our design specifications . . . but we’ve taken them for granted, we’ve left them to decay, and now I think we might be at that moment in cartoons where you’ve run off the cliff but you haven’t fallen yet.”

For a deeper view of Haidt’s ‘Tower of Babel’ metaphor about institutional decay, his recent Atlantic article Why The Past 10 Years Of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid is also worth a read.

In so many areas, from finance to business and from government to civil society, we seem to have one foot in the old world of hierarchy and authority, and one in the newly-emerging world of networks and influence. Far too many institutions and organisations require an upgrade to function effectively in the new world that is emerging.

Hierarchies vs Networks

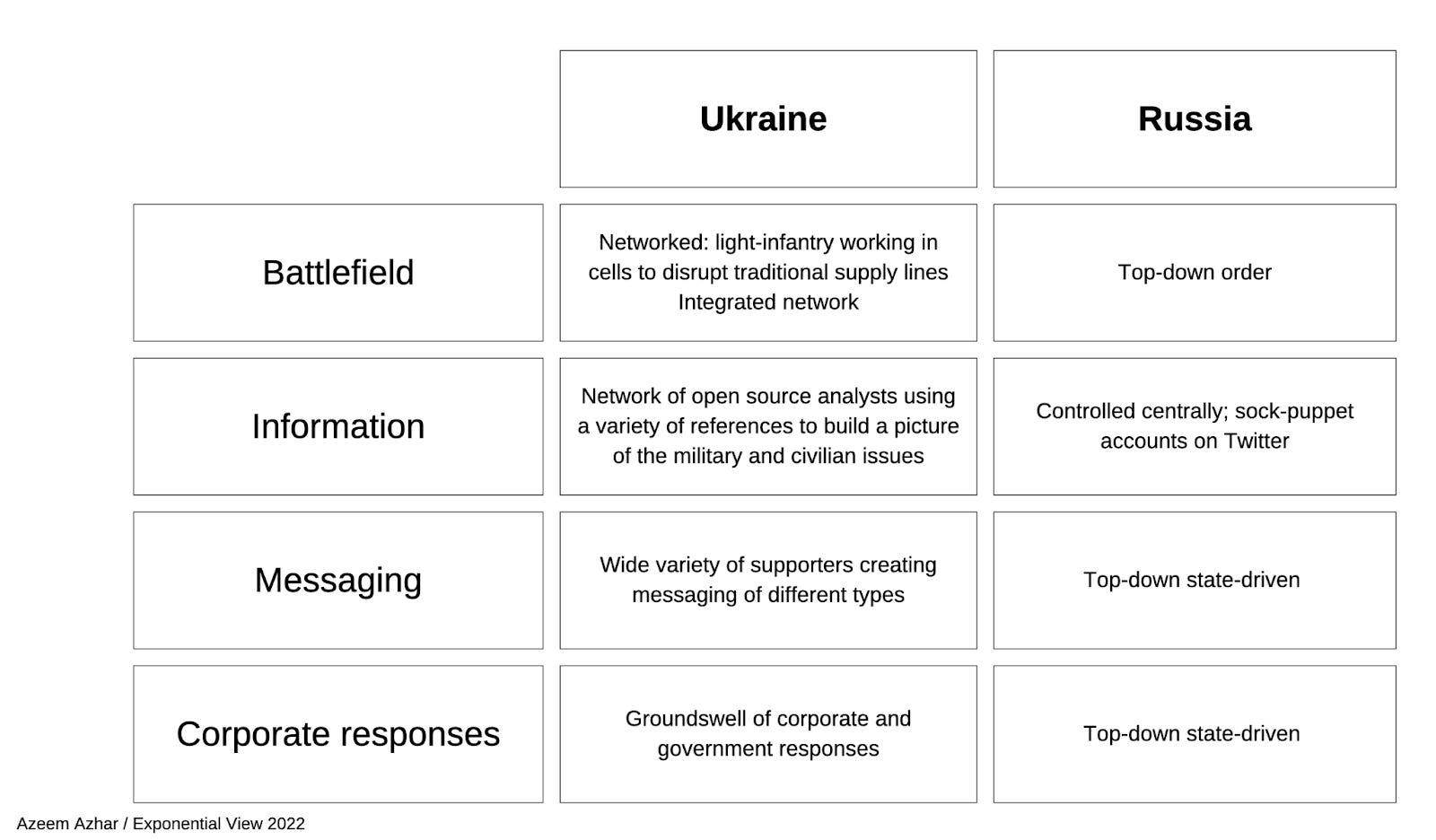

In his excellent Exponential View newsletter, Azeem Azhar recently used the example of the Ukraine war to illustrate the battle between hierarchy and networks as organising principles.

The Soviet economic system – exemplified by the corrupt and apparently ineffective Russian army it spawned – was strongly influenced by early C20th US business school thinking, and its industrialisation was lifted wholesale from US factory management practice, sometimes literally. In one of his many informative threads on the conflict, Kamil Galeev provides some historical background to this process, and highlights the significant vulnerabilities and dependencies on foreign technology this created:

In the corporate world, this echoes the fate of large conglomerates that came to view their hierarchical command and control management and planning system as both core competence and competitive advantage, and then proceeded to outsource technology, data and other functions that later proved to be far more strategic and less fungible than generic management.

Over-specialised, top-down organisational structures optimised to run like a factory production line are part of the problem many firms still need to overcome, even in the 2020s.

Re-wilding and the power of weak ties

In these ‘between times’, people often make sense of change by re-creating familiar aspects of the old world within the new one, such as illustrating email functions using a paper envelope icon, or continuing to create content in the form of A4 or Letter-sized ‘pages’ in ‘documents’ even when we hardly ever print them out.

In the hybrid working era, many managers have fallen back on the bad habits of memos and meetings as a way to maintain the illusion of control over their slice of the corporate hierarchy. Rather than go all-in on online collaboration, agility and autonomous working, many organisations have instead opted to re-create the worst aspect of office life – non-stop, back-to-back meetings – in their online and remote working rhythms. Not only does this make it harder to get actual work done, it also risks eliminating the serendipity of bumping into people and reduces our network to a subset of strong tie relationships among our immediate colleagues, as Lynda Gratton writes.

And while AirBnB is proudly celebrating its ‘live and work anywhere’ policy, Apple is busy fighting a rearguard action against remote working, perhaps partly driven by the huge effort it put into its new HQ building that was designed to promote more physical interaction. Some firms are even trying to recreate office surveillance for remote workers, as this piece on the worrying rise of so-called ‘bossware’ suggests.

As we keep repeating, the key question today is not where, but how we work. If managers can embrace online collaboration, service-oriented and distributed ways of working and write things down to make them shareable, then people and teams can do their work from home, office or client site, depending on what works best on a given day. This enables us to weave ties, relationships and networks between people and teams that can create a richer, more connected digital workplace that is less dependent on managers convening meetings to get things done. Work begins to flow.

A useful metaphor here, I think, is the notion of re-wilding in the context of work and business ecosystems that Stowe Boyd uses in this piece about the ecology of work. In moving from the industrial management model to something better, we need to focus on re-wilding our networks and ecosystems. Connected work systems are not only more efficient in energy and resource use than the old command and control approach, but also more adaptable, resilient and sustainable.

“Perhaps corporate leaders need to reconsider the ‘business as a machine’ mindset that places optimization of business processes above the agility and flexibility that underlies resilience. Instead of seeking to make the company into the leanest possible linear system—a strategy of reduction—leaders could instead aspire to looser, wider connections across the company, and an intentional diminishing of downward control. These are the hallmarks of deep resilience.”

Organisational design – and work systems design – will be an important battleground for the future of the firm, as well as other institutional upgrades we need if we are to avoid the problems that concern Jonathan Haidt and other observers of our changing societies.

Come Say Hi in Lisbon

Bonus link: more reasons to consider ‘Social Now’ in Lisbon as your next physical conference – all about creating high-performance teams in the hybrid era.