In large organisations today, the dominant form of work co-ordination is still old-fashioned ‘manual’ management and meetings, despite the existence of accessible, simple technologies that could solve this problem more effectively.

As The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson reported in a recent newsletter:

“I think we’ve hit the high point of max human inefficiency in white-collar work,” Jared Spataro, a vice president at Microsoft who focuses on artificial intelligence and work trends, told me. “It sometimes seems as if the modern worker spends more time talking about work than actually working.”

This is not just horrendously inefficient, it also crowds out real work.

“Altogether, the meeting-industrial complex has grown to the point that communications has eclipsed creativity as the central skill of modern work. Last year, another Microsoft survey found that the typical worker using its software spent 57 percent of their time “communicating”—that is, in meetings, email, and chat—versus 43 percent of their time “creating” documents, spreadsheets, presentations, and the like. Today, knowledge work is, quantitatively speaking, less about creating new things than it is about talking about those things.”

When I teach leaders how to create a culture and an architecture of collaboration in the digital workplace, I start from the assumption that most collaboration is passive, not active, and we only need to switch to active, real-time conversation (e.g. meetings, whether in person or virtual) if we need to clarify complex questions, work creatively together or just to socialise and catch up. For most other routine tasks, simply doing your work within a common platform that surfaces updates (e.g. a wiki or Notion) means that colleagues can stay updated and respond to your ideas without needing to schedule a call. Background sharing is the most efficient, polite and effective way of ensuring everyone is on the same page and has access to the same information.

Before we even apply AI and smart tech to the way work is done, the opportunity for addressing the inefficiency of work co-ordination is huge. Creating a personal agent that grabs updates from colleagues and synthesises them into a summary or overview is trivially simple today, and this one use case alone could enable a significant reduction in time lost to meetings. But as with so many other ‘obvious’ use cases for AI, the blocker is management culture, not technology. If we continue to tolerate needy managers imposing such huge interaction time costs on their teams, then nothing will change.

AI as Enterprise Software Disrupter

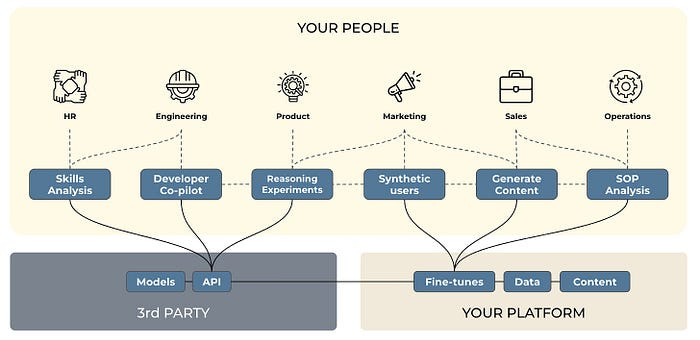

There are so many easily addressable opportunities like this for connecting the digital workplace more effectively, but companies will need to own more of their platform engineering to really get into the details and create their own solutions.

In the Death of SaaS, Aki Ranin predicts that AI capabilities will make companies less dependent on using third party SaaS platforms, which are often used like a sledgehammer to crack a nut:

This has gotten so out of hand, that we need SaaS to manage your SaaS bills. I’m not kidding.

Often SaaS tools fill smaller tactical gaps, where a whole suite like Salesforce, Hubspot, or even Shopify is complete overkill. With the help of AI, and soon by AI agents, you will build something yourself.

He cites the example of an intern at a YC startup who built an AI-powered invoice processing pipeline – in two hours (!) – rather than pay $16k for a.n.other SaaS subscription.

The beating heart of this software will be AI and LLMs. In some cases, these entire workflows might be automated, where no UI is needed, and AI just navigates a series of API calls to do the job independently.

Future startup AI OS by Aki Ranin

This chimes with something Larry Dignan shared recently: GenAI may be the new UI for enterprise software:

Enterprise software could be disrupted as category windows become collateral damage to generative AI. The scenario: Today’s go-to systems are relegated to plumbing as generative AI becomes the de facto user interface that democratizes data, insights, analytics and automation.

Elsewhere, Dignan also surveys some of the use cases large corporations are currently tackling, and the potential for them building and owning more of their own platforms and organisational operating systems is becoming clearer.

Agents and APIs over Apps

This new approach to developing small, local apps and automations in the enterprise will change the relationship between user interfaces, APIs and application logic. Rather than building many small software apps, each with their own interface, most automations will be API services or agents – similar to headless systems – that get called as and when needed by enterprise apps or by other agents or APIs as part of a multi-agent architecture.

Multi-agent automation within a single enterprise is on the horizon already as it makes sense to use specialised, small agents optimised for specific tasks and then chain them together to perform more complex actions and workflows. But it is still likely that, for many purposes, enterprises will eventually need access to 3rd party agents to deal with external data or services.

One paper that has been getting a lot of attention in this area is a proposal from a research group in China for an Internet of Agents framework to allow precisely this kind of interoperability:

The IoA is a platform resembling an instant messaging app, enabling communication and collaboration among autonomous agents. It tackles distributed collaboration, dynamic communication, and heterogeneous agent integration. IoA’s server manages registration, discovery, and message routing, while the client provides agent communication interfaces. Key mechanisms include agent registration and discovery, autonomous team formation, structured conversation flow, and task assignment and execution. The system uses a comprehensive message protocol for efficient interaction. For instance, agents collaborate to write research papers, form teams, assign tasks, and integrate contributions to achieve the final goal.

Architecture and Knowledge Abstraction

For this kind of organisational architecture to fulfil its potential, we will need leaders and managers to become more fluent in technology architecture and how this is becoming the basis of a new organisational architecture. Abstractions, service-oriented approaches, loops and layers are all more important mental models than tasks and workflows today.

Ben Read did a good job recently of explaining some of these concepts in The Critical Computer Science Principles Every Strategic Leader Needs to Know:

“Every company today needs to think of themselves as a tech company,” says Andy Wu, the Arjun and Minoo Melwani Family Associate Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School. “Whether you’re in retailing or you’re a law firm or a real estate company, technology is an important part of how businesses operate, and that can only increase going forward.”

We also need to organise our information and data using similar principles.

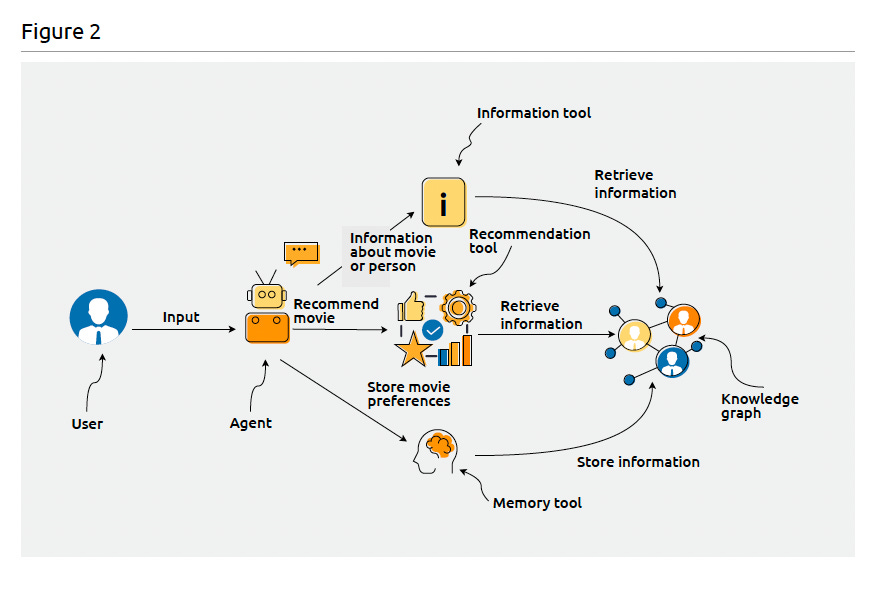

Cap Gemini’s Joakim Nilsson recently wrote about how knowledge graphs could play an important role in improving the reliability of Gen AI answers and to enhance unstructured data:

The Knowledge Graph acts as a bridge, translating user intent into specific, actionable queries the LLM can execute with increased accuracy and reliability. By allowing any user – regardless of technical knowledge – to inspect how the LLM arrived at its answers, people can validate the information sources themselves.

Multiple agent query templates in action. Credit: Cap Gemini

The coming together of AI, multi-agent systems, and knowledge graphs promises a real shift in how we work and collaborate. Confident leaders who embrace these innovations and the new organisational architectures they require will be able to unlock a world of efficiency and creativity that transforms not just our organisations, but the very nature of work.

We also offer AI experiences, workshops and talks for leaders and managers in large organisations who want to learn more about practical implementations of emerging technologies in their organisations.