One overlooked benefit of AI and smart technology is its potential to solve the problem of coordinating work and related communications in large, complex organisations.

We have studied better alternatives to the cascading hierarchy for decades, and in the hands of visionary leaders, models like cellular structures, the amoeba model of Kyocera that we wrote about last week, Spotify’s tribes, or WL Gore’s bounded autonomy approach can be very successful and yet much leaner and cheaper to run at the same time.

But in most organisations, hierarchy has two key technical advantages and one important socio-political feature that have until now outweighed its many disadvantages:

- Hierarchy is legible – in other words, you can read an org chart and navigate it to find the person or function you need

- Hierarchy is controllable – when urgent action is needed, the top of a hierarchy believes it has the levers to cascade aligned action throughout the whole organisation; and,

- In socio-political terms, it enables a winner-takes-all game for managers to succeed personally, irrespective of collective outcomes

In the literature, the most studied transformation from hierarchy to agile connected ecosystem is probably the story of Haier and its three-phase journey first to an inverted hierarchy, then a platform organisation and finally to an entrepreneurial ecosystem group structure based on that platform. This Rendanheyi model of mutual accountability has worked not just in the manufacturing sector where it began; it has also spread to other areas and sizes of firm, as this interview and case story about a small Italian comms agency by Emanuele Quintarelli at Boundaryless illustrates.

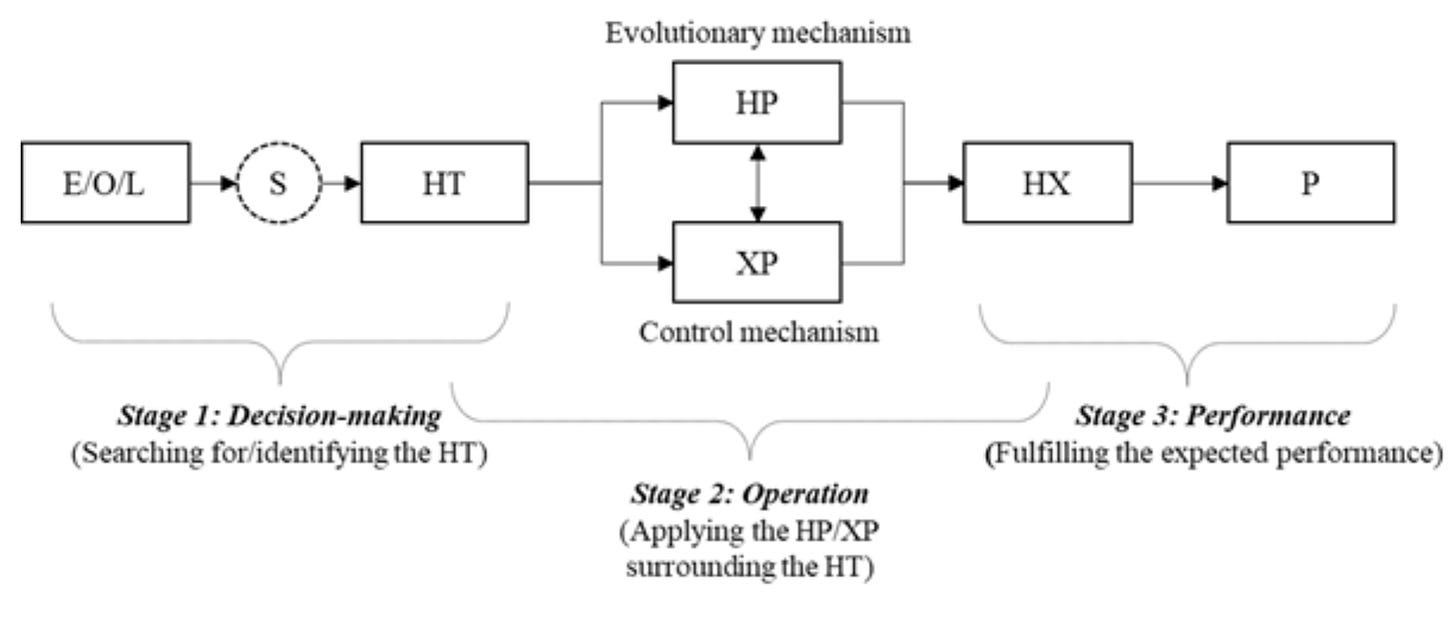

Elsewhere this week, European Business Review published an article on a related management theory (HXMT) that seeks to build on the success of Rendanheyi to create a fusion between Chinese management philosophy and modern international management thinking:

HXMT model from European Business Review

Legibility and Control Systems

So why do I think AI and smart systems could potentially make management innovation like this more viable? Essentially, because enterprise AI agents can do a better (and more real-time) job of ensuring legibility and control in an organisational system than traditional manual approaches to management communication and work coordination.

David Weinberger and Michele Zanini co-authored an interesting piece in HBR recently about the implications of AI for business that touches on this:

An always-on, real-time conversational space open to all (in particular those at the edges of the organization) can enable people to talk about what’s interesting to them, such as an incipient trend and how it might affect the industry. This platform might be the first place to note small signals, collaboratively make sense of them, and potentially usher in a strategic shift.

This is changing the sense of where the knowledge resides in the organization, from a cluster of designated experts, to something akin to a metaphorical “neural network” of transient conversations, many (though not all) initiated and put together by AI that’s connecting a wide and diverse set of people across every layer of the hierarchy. Some of the most valuable insights might well emerge when the system uncovers strong agreement — or constructive disagreement — between people in functions that often don’t see eye to eye, such as sales and R&D, or finance and HR.

This builds on the insights of the first social computing era, notably the idea of collaboration tools sharing signals in the background to improve our ambient knowledge of what is going on around us in the organisation. But, sadly, social collaboration didn’t become the dominant way of working in most organisations, who continue to bury knowledge in documents, hide data in spreadsheets and dilute their ideas into PowerPoints that are presented in ritualistic meetings.

However, if instead of relying on people changing their behaviour, or explicitly choosing to share and collaborate, we use agents to gather, aggregate and distribute all this operational information and knowledge, then perhaps we can solve the work coordination challenge with software instead of middle managers.

And this could also support more fluid, adaptive organisational structures, such as temporary hierarchies, peloton leadership or ‘teams of teams’ in specific contexts. As Weinberger and Zanini noted:

A century ago Mary Parker Follett, a pioneering management thinker, wrote that “one person should not give orders to another person, but both should agree to take their orders from the situation.”

We now have the ability to address situations at an unprecedented level of detail and nuance. This means not just more efficiencies, but authority flowing to the edge of the organization where people will have the information, skills, and tools to make the right tradeoffs, one decision at a time.

Rather amusingly, somebody has already experimented with the idea of programming such a multi-agent coordination system with the corporate culture of the host organisation – or in this case, the culture of well-known big tech firms (the idea came from learning about Conway’s Law).

Here are some key takeaways I learned after organizing groups of AI agents as if they were in companies like Apple, Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and more:

- Companies with multiple “competing” teams (i.e. competing to produce the best final product) like Microsoft and Apple outperformed centralized hierarchies.

- Systems with single points of failure (for example, one leader making important decisions) like Google, Amazon, and Oracle underperformed.

I can’t wait to see agent prompts along the lines of “do this in the style of a big 4 associate who wants to make partner – take all the credit for your team’s work and throw some other agents under the bus to assert dominance” 😉

And on the subject of relying on junior staff in the professions, I am reminded of this recent FT piece: Automation is coming for private equity’s junior roles:

One of the really striking things about the story of spreadsheets in the 1980s, particularly in the case of PE, is that spreadsheets allowed financiers to see and imagine differently,” said William Deringer, a historian at MIT and a former investment banker. “I think it is quite possible that new automation tools for financial analysis might offer similarly new kinds of vision and imagination.”

Using agents to automate analysis could be at least as transformational as the rise of spreadsheets in seeing things differently, but we also need to remember one of the paradoxes of automation. Sometimes, repetitive grunt work is a key part of the learning experience for people coming into the firm, whether it is long nights of desk research or staring at hundreds of spreadsheet P&Ls to get a feel for the data in your chosen field. If we automate all the grunt work, we might need to find new opportunities for learning and development. There is something to be said for throwing people in the deep end – it seems to be a very human route to excellence in sport, business and other fields.

Visibility in the Connected Organisation

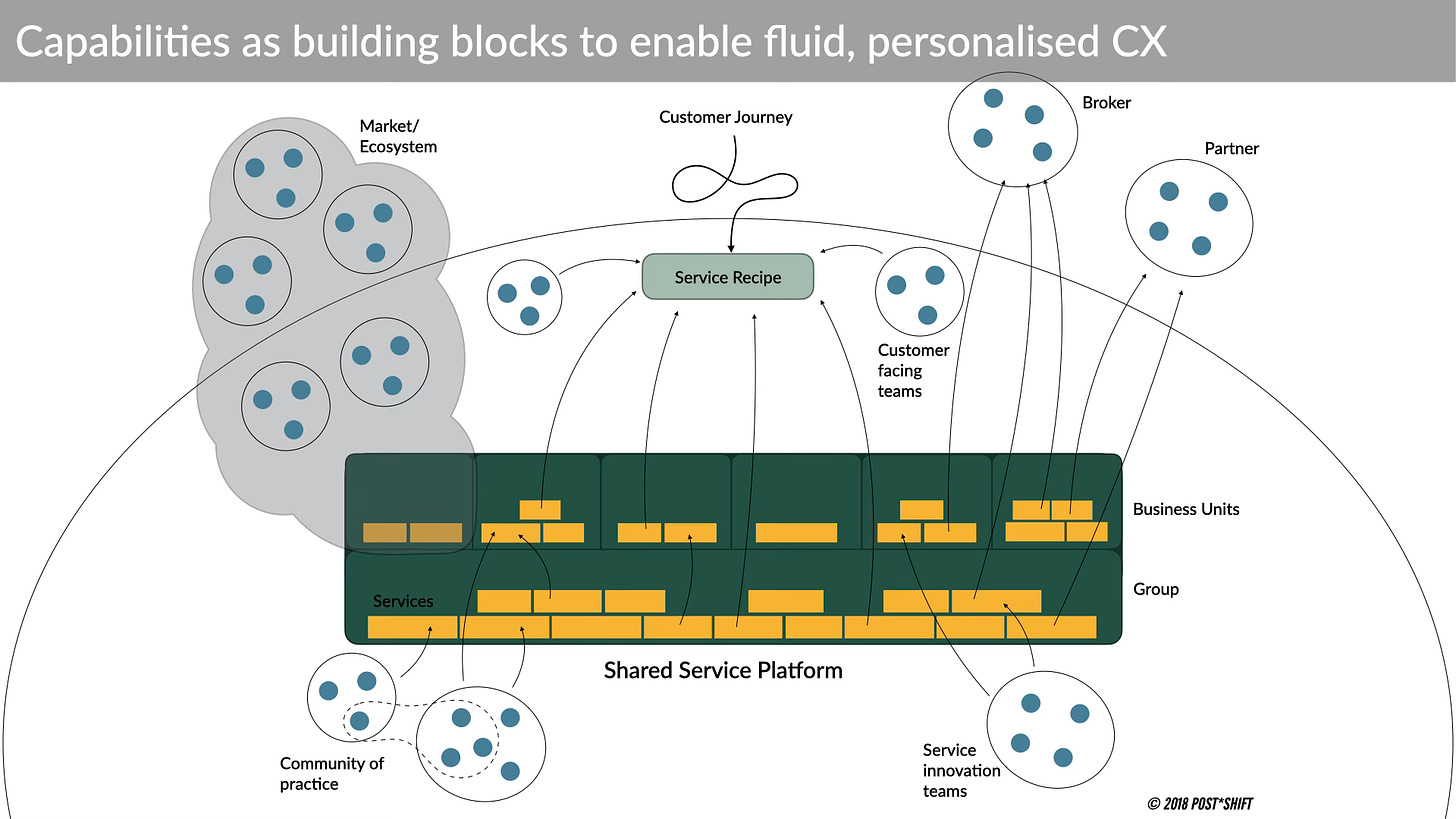

Looking at the example of Haier mentioned earlier, perhaps the key technical innovation was their shift to a platform organisation. This is not only the best reference architecture for a modern, agile organisation – it is also the most logical, software-like way of orchestrating and connecting all the various AI services, automations and agents that we expect will be part of the fabric of smart organisations in the future.

There are already platform-based organisations using this model today, and this requires an organised approach to platform engineering, as outlined in this piece from CIO magazine. But platform engineering within a traditional organisation structure is hard.

Using AI and automation tools, it is becoming easier for platform engineering teams to orchestrate and automate their own services and use continuous testing and monitoring to look after them, but they often lack visibility on the other side of platform to know enough about how their services are used and combined to deliver value.

Perhaps we will see agents used to extend the platform engineering model from the supply side to the demand side to improve the feedback loop between service creation and usage.

A shared service platform supporting fluid customer experience (Postshift)

Another example of a process that is key to supporting connected organisational structures that go beyond simple hierarchical control is the work we do with skills and capability mapping to ensure the organisation can build a real-time picture of its emerging digital capabilities, where they are, and how they can be combined and connected. We started running this process manually, and then realised we could simplify the data collection using bots to ask people and teams what they had and what their gaps were.

Going forward, I am hopeful we can build an organisation-wide capability and skills map using agents that do the analysis and extrapolation themselves, and then sense check this with the relevant people and teams to provide human oversight. This would significantly reduce the time and effort required to build a capability map fast enough for it to be immediately useful.

I think these are the kinds of new approaches to organisational development and heath monitoring that multi-agent AI models will make possible, and this could be a key advance in addressing the coordination, legibility and visibility challenges that non-hierarchical organisational structures and systems face today.

If you would like to learn more about how we help organisational transformation and AI adoption, check out our website