We are witnessing what looks like a major transition in the way we approach software development, and this brings both potential benefits and risks for organisations. But we should not think about this only as a new way to build apps and products. In a world where organisations are becoming software, this shift could accelerate the transition from manual process management to smarter, more automated internal systems.

Although this will change the balance of skills and capabilities required to make things, it would be a huge mistake to ignore the human factors involved in choosing what to build, where, how, and what kind of experience and impact to deliver for people.

All your (code)base are belong to us

If you have not yet experienced the future shock of watching an AI model build a working app based on a simple description of what you want it to do, then a good place to start is Simon Willison’s excellent guide to how he uses LLMs to help write code, taking into account his words of warning:

Using LLMs to write code is difficult and unintuitive. It takes significant effort to figure out the sharp and soft edges of using them in this way, and there’s precious little guidance to help people figure out how best to apply them.

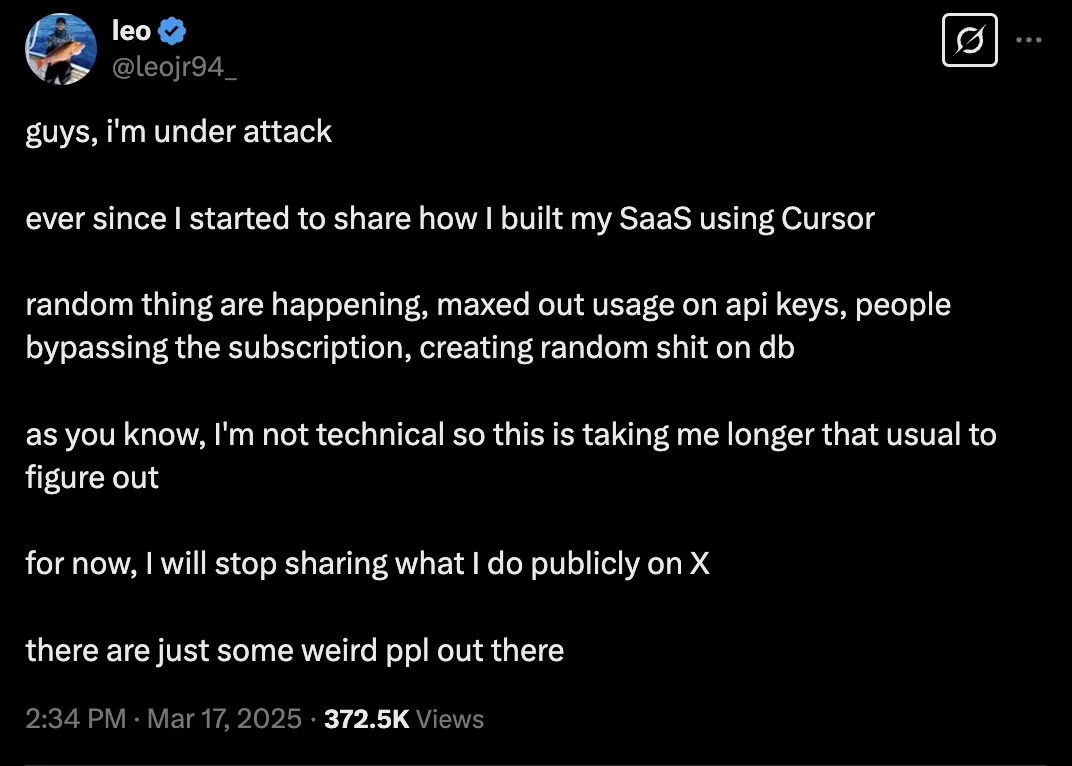

There will be a lot of tears, and not all of the joyous kind, as this blue tick Twitter user found out:

Twitter screenshot from @leojr94_

AI-assisted coding is potentially very impactful in terms of how we use technology and who uses it (democratising access), but also in terms of the economics of building things and doing work.

Azeem Azhar, writing about the rise of AI reasoning models, concluded last week:

There is an economic earthquake waiting to happen. GPT-4o managed just 30% on SWE Bench’s real-world coding tasks, while Claude 3.7 Sonnet — a reasoning model —achieved 70%. That 40-point gap is already reflected on the bleeding edge of our economy: 25% of the latest Y Combinator startups generate 95% of their code with AI.

Software engineering might be the most obvious early frontier. Developers sit right next to AI’s beating heart—but other analytical fields are following closely behind.

Ethan Mollick has a long track record trying out new AI capabilities with a view to discerning what they might mean for the future of work and learning. His recent post Speaking things into existence related his own experiments in building apps with AI coding tools, and he was slightly more sanguine about where we are today:

Work is changing, and we’re only beginning to understand how. What’s clear from these experiments is that the relationship between human expertise and AI capabilities isn’t fixed. Sometimes I found myself acting as a creative director, other times as a troubleshooter, and yet other times as a domain expert validating results. It was my complex expertise (or lack thereof) that determined the quality of the output.

The current moment feels transitional. These tools aren’t yet reliable enough to work completely autonomously, but they’re capable enough to dramatically amplify what we can accomplish.

At the other end of the spectrum, OpenAI’s Chief Product Officer Kevin Weil, fresh from the launch of new tools for creating AI agents, is also predictably bullish about AI coding, announcing in a podcast interview this week:

“This is the year that AI gets better than humans at programming, forever. And there’s no going back.”

A new golden age for experience & service design?

But wait a second.

Perhaps this is not such a done deal as it might seem, and in fact what we are seeing is a re-configuration of the respective roles of people and software in the process of building technology products and services, rather than outright human replacement.

Tim O’Reilly is an experienced watcher of tech trends, and he reached back to an analogy about the early PC era to explain why he thinks creativity, values and taste will continue to drive human preferences, and by implication increase the value of non-automated outcomes:

Whatever changes AI brings to the world, I suspect that those three things—creativity, values, and taste—will remain a constant in human societies and economies.

Abundant expertise may be the booby prize when that expertise is based on consensus opinion, which, by the nature of LLMs, is their strong suit. This came home to me vividly when I read a paper that outlined how when ChatGPT was asked to design a website, it built one that included many dark patterns. Why? Much of the code ChatGPT was trained on implemented those dark patterns. Unfortunately neither ChatGPT nor those prompting it had the sense to realize that the websites it had learned from had been enshittified (to use Cory Doctorow’s marvelous turn of phrase).

In a world where code is abundant, we should expect good quality user experience design, service design and understanding what people want and need to increase in value.

Twenty years ago, when businesses thought web software was magic, it was not hard to get them to pay six figure fees for systems that are commodities today, but it was often more difficult to persuade them to pay for design or user research, let alone things like copy-writing and adoption or change management relating to the product’s use. This is perhaps partly why products like Flickr and Slack stood out, as their design style and wonderfully human copywriting gave them character above and beyond the simple technology they used to facilitate human connection.

Since then, the world of enterprise software and systems has been defined by lowest-common-denominator one-size-fits-all monoliths that are universally hated, but were sold on the basis of cost efficiencies rather than how they improve the experience and productivity of work.

One of the big opportunities here is for organisations to gradually take ownership of their work and service platforms, building small apps and connective systems that do exactly what they want in a way that suits (or even, dare I say, delights!) their people.

The coding and the models are being commoditised to an extent; but experience and service design are not. That is where the skills and specialist local knowledge will be needed to make the most of what an organisation already has in place. If you can imagine it and sketch it, you can build it, whether you are a designer, a manager or a team member with an improvement idea. And it belongs to the organisation, rather than its SaaS landlords.

We will deep dive into new AI-enhanced service design capabilities next week.

Humans gonna human

The Digital Data Design Institute at Harvard recently published some research entitled A Human Touch: Why AI Can’t Fully Replace Empathy in Social Interactions that suggests people behave differently when they are communicating with a human versus a machine.

“[P]articipants who believed they were communicating with a human […] felt more positively and less negatively as a result, and believed it to be more helpful and supportive.” [1]

The research team found that when participants believed they were interacting with a human, they rated the empathetic responses more positively across various measures. This was true even when the responses were actually generated by AI in both conditions. The perception of human interaction led to higher ratings of empathy, support, and a greater desire for continued conversation. This suggests that the mere belief in human interaction significantly enhances the perceived value of empathetic exchanges.

I wonder how this phenomenon will play out in the many uncanny valley scenarios we will face with AI tools?

Understandably, much of the analysis and reporting of AI developments has come from those people best placed to follow and understand this dizzyingly rapid technological evolution. But we should probably seek to balance this with more consideration of the issues and challenges around how human cultures (including work culture) co-evolve with the technology.

Henry Farrell has published a substantive contribution in this direction – a paper for Science co-authored with Alison Gopnik, Cosma Shalizi, and James Evans entitled Large AI models are cultural and social technologies:

Our central point here is not just that these technological innovations, like all other innovations, will have cultural and social consequences. Rather we argue that Large Models are themselves best understood as a particular type of cultural and social technology. They are analogous to such past technologies as writing, print, markets, bureaucracies, and representative democracies. Then we can ask the separate question about what the effects of these systems will be. New technologies that aren’t themselves cultural or social, such as steam and electricity, can have cultural effects. Genuinely new cultural technologies, Wikipedia for example, may have limited effects. However, many past cultural and social technologies also had profound, transformative effects on societies, for good and ill, and this is likely to be true for Large Models.

And of course, this is a very nuanced area that we hope will not end up as a typically polarised debate between boomers and doomers, as the authors point out:

The narrative of AGI, of large models as superintelligent agents, has been promoted both within the tech community and outside it, both by AI optimist “boomers” and more concerned “doomers”. This narrative gets the nature of these models and their relation to past technological changes wrong. But more importantly, it actively distracts from the real problems and opportunities that these technologies pose, and the lessons history can teach us about how to ensure that the benefits outweigh the costs.

Although organisations of all kinds are busy writing cheques for anything that mentions AI, agents and automation, I hope they will consider reserving some investment of time, money and thought for the many as yet unexplored questions of how they create a relationship between people and AI that augments, elevates and extends human capabilities that can take our businesses, governments and other forms of organisation to a new level of productivity and value creation.