The words ‘change’ and ‘disruption’ are seen by many within the tech sector as unalloyed good, but there are many situations where seeing a problem and breaking down the old system are easier by orders of magnitude than building something new in its place. And of course, in critically important areas such as government, banking, the food supply, energy and medical care, continuity of service is far more important than a complete service re-invention that risks services that peoples’ lives depend upon being unavailable.

No doubt many government institutions and structures are badly in need of reform, but reports from insiders on the DOGE power grab in the Unites States are alarming to put it mildly, and it looks more like destruction than disruption, with little concern for the many unforeseen consequences that such radical, unplanned action will inevitably throw up. For example, it is a reasonable assumption that giving root access to Musk’s young acolytes for the Treasury will result in one of the most protected US national datasets falling into the hands of the intelligence services of at least one nominal foe of the USA.

The CEO of Palantir – poster child for dystopian uses of AI and expected beneficiary of this destruction – was quoted in the Financial Times this morning as saying:

“Disruption at the end of the day exposes things that aren’t working. There’ll be ups and downs,” Karp continued. “This is a revolution. Some people will get their heads cut off . . . We’re expecting to see really unexpected things and to win.”

You can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs, but you can certainly make one without taking all the chickens outside to have them shot for imagined thought crimes, and then burning down the farm.

Chesterton’s Fence is an oft-quoted change principle that can be summarised as:

do not remove a fence until you know why it was put up in the first place.

This is a lesson that has been learned many times over in the field of digital transformation.

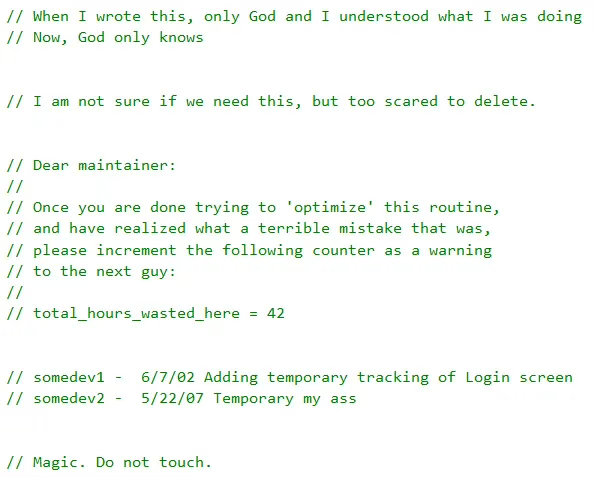

Banks and insurance companies sometimes try to tackle the limitations of their legacy systems by building a net new platform, and this often fails disastrously. Seasoned developers tell stories of how speeding up a function (must be good, right?) can actually bring down a complex IT system by triggering a race condition or some other unforeseen repercussion. There is a lot of code out there with comments to the effect of ‘we don’t know why, but if you remove this loop the system crashes’. The same is true for what is sometimes called junk DNA in the human genome – it seems to do nothing, but if you remove it, we might die.

found code comments shared on Stack Overflow

Understanding the workings of government functions, large companies, or institutions requires a skillset closer to archaeology or geology to appreciate the dependencies between various layers of process, history, technology and even behavioural norms before taking radical action. Or, if we are feeling bold, we might look to systems thinking and try some safe-to-fail probes to see what happens next. And yet, time and again we see people – typically hubristic individuals who are unfamiliar with how the system works – point at institutions or systems and assume they can tear it down and build a better one without any relevant knowledge or experience.

The operation was a success but the patient died

In our organisational transformation work, despite feeling immense frustration with the bureaucratic and managerialist nature of many organisations, we always pair up a transformation roadmap with a transition plan that starts from today’s reality and gradually shifts towards new capabilities and affordances without harming performance – or better still, with each stage of the transition making the old system work slightly better.

When we are dealing with the kinds of major change that AI technology could bring to peoples’ jobs, the way we relate to each other, or to oversight of key functions, it is unwise to jump in with both feet based on the promises of a vendor or a developer and replace the entire customer service function with chatbots, or swap out internal audit with an agent that can perform real-time analysis of the finance platform. Sometimes when something is gone, it never comes back. Twitter might once have been a dysfunctional clown car that fell into a gold mine, but after it was gutted by Musk using the same playbook he is following for DOGE, it is more like a broken down vehicle with neither humour nor a gold mine.

A good example of something that is easy to destroy but hard to re-create is what companies loosely call ‘culture’, which is really a pointer to elements as diverse as sense of purpose, behavioural norms, ethics and values, and expectations of inter-personal relationships.

If private equity owners – or even your own CFO – decide that your people are just messy but fungible resource containers, and break up high-performing teams to outsource individual tasks to low-wage jurisdictions, or just contract out whole functions that are really part of your core competence, then this is likely to be an unrecoverable mistake. Boeing is a good contemporary example, but there are many others. Similarly, companies that jump feet first into replacing people with AI without consideration of its impact on their employees or customers risk creating unforeseen harms that outweigh short-term savings.

With so many financial incentives for bad or misguided actors to enjoy short-term personal ‘wins’ at the expense of long-term collective harm, we should expect to see more critiques and push-back on potential AI societal risks, and leaders need to listen and make their own minds up rather than blindly accept a binary, polarised debate where AI is either saviour or devil. Premature and overreaching regulation by the EU could be harmful, but so too could MAGA-style deregulation and the absence of reasonable consumer or employee protections.

There are emerging initiatives to bake pro-social principles into AI. There are also growing fears that of the risk that AI will allow ‘inhumane treatment at a distance’, such as this article by Eryk Salvaggio, exacerbated by recent events within the US government. Perhaps some of these fears are overblown, but if we want a smooth AI transition in business rather than disruption for its own sake, then it is worth at least considering all angles. Even the Vatican is trying to make sense of AI and the explosion of knowledge.

As Salvaggio puts it:

It’s clear to me that Musk and DOGE will embrace a shift in how we use AI outputs. This will move AI outputs from prescriptive – recommending a course of action, based on an analysis of data, such as flagging an insurance claim for review – to autocratic: a singular source of authority, where the text it generates becomes directly actionable as a decision without human intervention, such as rejecting an insurance claim outright.

World-building in times of change

It may sound counter-intuitive coming from an advocate of programmable organisations, but creating an organisation that lasts is more an exercise in world-building than it is in making money. The lists of the world’s oldest companies contain many companies who pursued their own ways of doing things, with their own sense of excellence or integrity, regardless of how the world around them changed. The kind of companies that look after their people and quietly go about their business, rather than the kind that flip straight from ‘Lean In’ to ‘more masculine energy’ to please a tyrant.

Banco Santander navigated the Franco regime in Spain and went on to build a powerful group partly based on this experience. In Brazil, during the hyperinflation of the 1990’s, Riccardo Semler’s pioneering management culture was key to enabling Semco to survive and go on to greater success.

Companies are involved in world-building whether they realise it or not, and the advent of AI and agentic automation gives them tools and abilities that can be used to create either more pro-human or more anti-human worlds than the dreary people-as-cogs-in-the-machine stereotype of the Twentieth Century corporation. Perhaps they need fewer people than today, but if they create an environment that can attract and reward talent and engender loyalty to their mission, then this ‘culture’ will be a huge asset in times of increasing volatility and political instability around the world.

Even if corruption becomes the norm in government, the loss of professional standards in areas such as law and accounting would have such long-term implications for the business environment that we can expect these professions to at least try to maintain their integrity. Or to take another example, if a company’s customers are young people in urban areas, then even if the government is trying to make racism and sexism acceptable again, leaders will need to preserve modern values inside the company’s walls if it is to engage successfully with those customers.

Precisely because AI will allow us to automate and orchestrate the basic processes and operations of many businesses, it will also create both the space and the need for companies to differentiate themselves based on how they work, their culture, their people and their stakeholder impact, just as the best long-lived companies did before them. Being intentional and considered about the kinds of norms and defaults and ‘how things are done around here’ will be an advantage for those who get it right. Only the desperate need to work in an atmosphere of fear or denunciation.

Leaders and managers will also need the knowledge and confidence to assess the hidden default settings and cultural assumptions that AI tools bring into the worlds they are building, and be intentional in choosing or rejecting them based on suitability for what they are trying to build. And of course the really hard bit is designing human-AI hybrid workplaces, where we can use these magical tools to elevate and augment human capabilities, rather than just replace them.

If today’s aggressive disruptors really wanted to learn how to reform complex institutions, they might dive into the field of cybernetic systems, where thinkers have been trying to imagine pro-human automated control and management systems since the 1940s. Henry Farrell’s commentary on recent events is an interesting and balanced read on where cybernetics could help and where it also risks falling into fantastical thinking.

I am hopeful that we can merge this domain knowledge with modern software thinking to update management thinking in a way that could led to some wildly successful, but also resilient and socially-useful new or reformed organisations emerging from the emerging enterprise AI transformation. But it’s going to be quite a ride.