2024 looks set to be a big year for enterprise AI adoption, but we need to think long-term and not be driven by the hype or the backlash.

It looks like 2024 will be the year when GenAI, automation and smart systems gain a strong foothold in the enterprise. But we might already be seeing signs of the inevitable pushback and disillusionment with GenAI being applied to everything from student essays to fake influencers to sassy customer service chatbots.

Simon Willison has shared an informative summary of what we achieved in 2023 – and it is a lot. Yes, the promise of AI has been over-hyped and under-analysed, as is always the case, but there is plenty of real value in the use cases to which AI is in the process of being applied. It is a big shift, just as social networking was from 2002 onwards, and the web before that. Yes, it might be attracting crypto bros who see a quick buck in building infinite numbers of pointless GPT wrapper apps that add no value (hence the acronym FICTA – failed in crypto, trying AI), but again, these cheap tricks and get-rich-quick schemes are part of every major shift.

I believe what is emerging in enterprise AI has the potential to accelerate the path towards smart organisations that go beyond the limits of the C20th corporation.

But first, we will need to navigate through the trough if disillusionment in the famous Gartner Hype Cycle, and start to value the basics, the long-term marginal gains and the prosaic low-scale automation use cases that will be part of the journey towards AI adoption.

Enterprise AI Lowlands

The first and most obvious areas of adoption in organisations is using GenAI to assist with content development and communications. At the same time, I expect we will also see a proliferation of bots that help people find things and solve repeatable process problems.

This will also have the effect of rejuvenating the low-code/no-code movement inside organisations, by making it trivially easy to prompt GPTs into developing prototype services, bots, agents and apps to solve very specific problems.

ZDNet recently talked about employees being both consumers and developers of enterprise AI apps, and I think that captures the potential quite well.

Microsoft’s Co-Pilot studio looks interesting. I look forward to seeing what it can do.

We will need a lot more digital confidence and knowledge within non-tech companies if we are to fulfil this promise, so we should expect a lot of focus in 2024 on Digital Academies and more imaginative approaches to on-the-job learning.

We might also want to think about moving beyond the limits of legacy user experience, which was driven by legacy technology constraints. Robot Process Automation (RPA) was always a transitional technology to help software bots fill in badly-designed enterprise apps and forms, rather than actually automating the service for real. But it continues to endure, with the addition of process discovery – essentially watching the forms and process steps humans use to get their work done and then using RPA to automate the input. It would be better to invest in net new smart digital services. Also, the addition of a new AI key to Microsoft keyboards is a good moment to pause and consider the ways in which our tools and input devices were designed for a workplace that no longer exists, So perhaps we can start to think more widely about the UX challenges associated with interacting with AIs.

Looking slightly further ahead, we should consider if we risk unintended consequences from automating or abstracting away all the boring stuff. In professions such as law and accounting, the realisation that new joiners learn their trade on the boring bits in the weeds of Excel and Word has been one factor holding back greater automation. How will they learn if all that is automated?

This reminds me of a little story Venkatesh Rao shared about the risk of knowledge loss if we do everything with (still not actually intelligent) GPTs and no longer invest in human innovation to tackle hard problems.

Enterprise AI Highlands

It is harder to know where we go from there, and how the big picture will look for AI in the enterprise, but I think the general direction of travel is towards the programmable organisation.

This is touched on in the ZDNet link above, which quotes a Deloitte report on AI:

The time could be ripe for a blurring of the lines between developers and end-users, a recent report out of Deloitte suggests. It makes more business sense to focus on bringing in citizen developers for ground-level programming, versus seeking superstar software engineers, the report’s authors argue, or — as they put it — “instead of transforming from a 1x to a 10x engineer, employees outside the tech division could be going from zero to one.”

Future applications are likely to be built on English or natural-language commands, versus Python or Java, they predict.

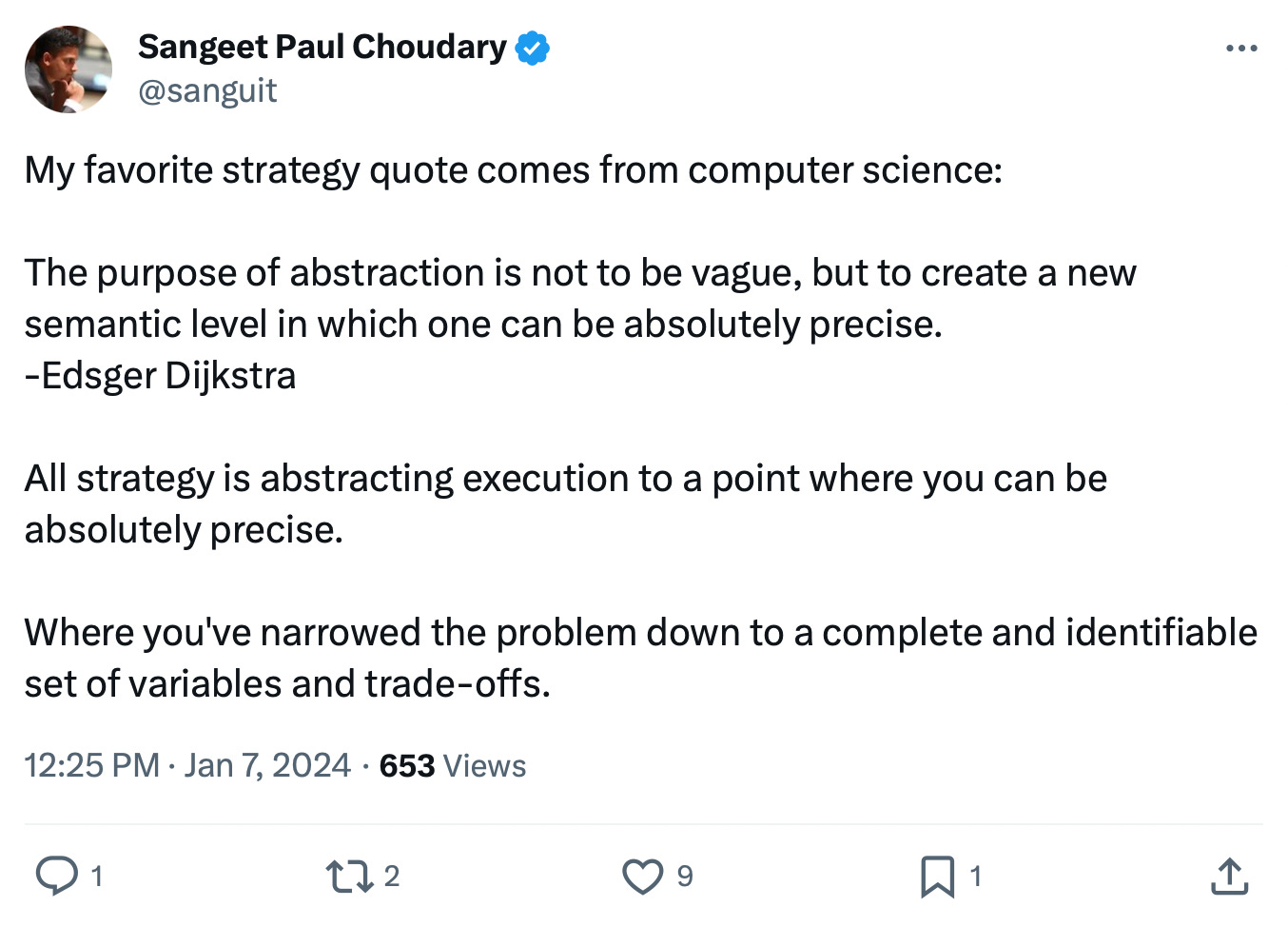

This is the potential that I find most exciting. Think of the way computer languages evolved to create more abstraction layers between the user and the underlying code operations, so that we could do more with less. Extrapolate that trend line out towards natural language controllers and you can imagine a programmable organisation where you can spin up a team space, apps and design and build the processes needed to operate, simply by describing what you want.

But, in a way, this is still in the realm of dealing with the boring stuff – the background processes and systems that organisations need to function. The real win is augmenting human creativity and vision by finding the right combination of background automation and human innovation and personal contact.

In The Case for Cyborgs, Alice Albrecht muses on how this might be achieved, but also warns not to treat humans as machines themselves:

We’re not just bits of intelligence bouncing through the world. We have complicated emotions, and nuanced and unspoken social hierarchies. We act irrationally and pursue goals that may not be in our best interests. We don’t exist within the clean confines of an operating system or a laboratory—we act and react in a highly variable world. Creating a machine that can score well on one-off benchmarks doesn’t mean it can read—or care about—morals or social cues. But missing these aspects of human behavior puts AI at a disadvantage, especially as we move beyond the chat box and into the real world. No number of YouTube videos can replace what one learns from physical exploration and social interactions.

We are already polluting the well of human discourse with obviously vacuous GPT-written articles that were training on already-terrible writing forms produced in the social era, intended to overwhelm search engines with volume rather than quality to win those all-important clicks. We are already growing tired of AI-generated images that somehow look quite similar, and of perky summary articles that all have the same structure but mask their errors with confidence. These, and other failures to live up to the hype, will be part of the coming backlash. But having seen a few of these cycles, the backlash is often no more material or meaningful than the hype.

Ignore both and build real things that help people do their work better.