The end of 2024 is seeing a flurry of announcements and releases that will shape the way organisations use AI tools and tech in 2025. We will look ahead to what that might mean in practice in our final newsletter of the year, a couple of weeks from now.

But first, what do these new developments mean for those of us interested in the practical implementation of AI as part of enterprise transformation, and ultimately the idea of the programmable organisation?

The debate about whether LLMs alone can achieve sufficient progress towards “real” intelligence looks increasingly settled, and hopefully this will encourage smarter innovation than just brute force scaling of compute, where the winner is whoever can create the biggest GPU cluster. The current state of the art still uses LLMs, but it builds on their ‘stochastic parrot’ methods to add more context, reasoning and testing. This may also be an important step on the way towards constructing world models.

Matthew Harris recently wrote about this shift, noting that:

“The tech industry is evolving beyond a singular focus on the AI scaling laws or the Transformer. … With the reverse hockey stick of model scaling leveling off into more of an S curve, the best thing we can do is promote open source model technology to continue to accelerate AI research and advancement.”

Google’s rush into AI-enhanced search using LLMs produced patchy results and served as a good demonstration of the need for contextual understanding, rather than just textual pattern matching. The company clearly faces challenges from AI, but even before the rise of ChatGPT, Google’s economic model had significantly degraded the quality of its search results. Nonetheless, Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai told the NYT Dealbook event to expect better results next year:

“I think you’ll be surprised even early in ’25 the kind of newer things search can do compared to where it is today”

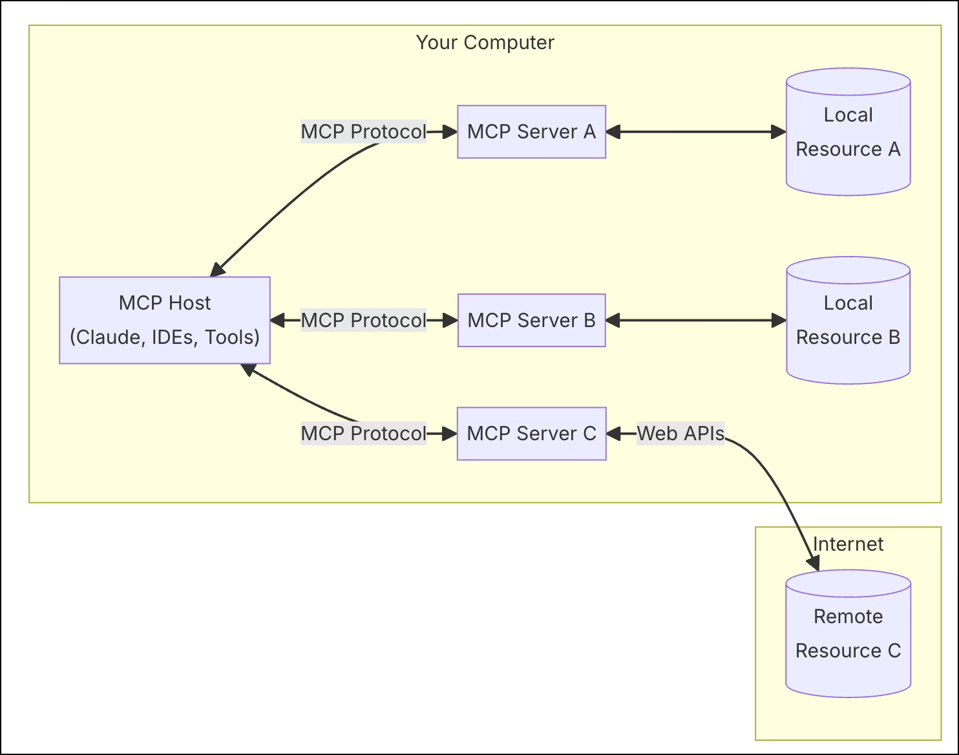

Anthropic recently announced their Model Context Protocol, which aims to provide a standard interface for LLMs to interact with other apps, for example databases that contain important context for an LLM to consider:

“As AI assistants gain mainstream adoption, the industry has invested heavily in model capabilities, achieving rapid advances in reasoning and quality. Yet even the most sophisticated models are constrained by their isolation from data—trapped behind information silos and legacy systems. Every new data source requires its own custom implementation, making truly connected systems difficult to scale.”

The adoption of this open protocol could have a similar galvanising effect as SOA (service-oriented architecture) protocols had on enabling better, more fluid enterprise IT integration in the early part of this century.

Anthropic’s diagram of the MCP in action

Disney’s Fantasia

Turkeys, Christmas and Organisational Prayer Wheels

It seems uncontroversial at this point to accept that a whole slew of repetitive processes and tasks will switch to digital labour, whether software agents or physical robots.

A recent report suggests 10% of South Korea’s workforce is now a robot. And even the lowest rewarded human labour such as focus groups and research participants is now at risk of automation, as New Scientist reports: AI simulations of 1000 people accurately replicate their behaviour.

But what of the skilled roles – and also the less skilled but politically powerful management roles – that make up the middle tier of our organisations today?

One optimistic argument for greater use of AI and automation in the enterprise is that this will enable individual contributors to do more with less, whilst significantly reducing the management overhead inherent in current coordination systems. Humans in charge, and free to do their thing whilst smart tech does the boring stuff that many middle managers do today.

In this vision, the Model Context Protocol developed by Anthropic would be very useful in enabling any organisation to integrate internal sources of data, policy and knowledge that could help regulate the army of AI agent brooms that do the connecting, reporting and sweeping up. And the increasing ability of AI models to test and question their initial responses – evaluating them against stated goals and expected outcomes – could increase their reliability and relevance enough to be trusted in most contexts where we currently accept a lot of human error and self-serving management bias.

However, the second adoption challenge highlighted in the FT piece should be taken seriously. Despite recent evidence in Europe and the USA that turkeys will enthusiastically vote for Christmas, even cheering on the chef as they sharpen the knife, it would be unwise to assume that managers will do the same.

I have always regarded workplace theatre and ritual as naturally occurring wastefulness that we can all agree should be reduced in favour of value-producing activities. But if you step back, squint slightly, and apply Stafford Beer’s heuristic The Purpose of a System is What it Does, you might come to a different conclusion, namely that bureaucracies are socio-political systems run for the benefit of their custodians and guardians – a kind of safe adult day care where sharp-elbowed conformists vie for influence and budgets to spend.

Is it inevitable that AI will eliminate this wastefulness and enable creators and contributors to take centre stage and do their best work? Perhaps not.

In fact, Henry Farrell makes the opposite argument – AI could in fact become a super-spreader of management BS because it is just so good at making it. Here he describes one of the four principal use cases he imagines AI will fulfil in a thoughtful post that is worth the time to read in full:

Organizational Prayer Wheels … This is an argument that Marion Fourcade and I have made already at moderate length. LLMs are like motorized prayer wheels for organizational ritual. Sociologists like Marion have made the point that a lot of what organizations do and demand from people involves rituals of one sort or another. Many meetings serve no purpose other than demonstrating commitment to the organization, or some faction, section, or set of agreed principles within it. Much of the written product of organizations has a ritual flavor too – mandatory statements, webpages explaining the mission, end of year reports and the like. These are exactly the kind of thing that LLMs are really good at generating – expected variations on expected kinds of outputs. As we say in the Economist.

That’s a sobering thought, and something to be aware of as we continue to pursue the goal of smart, programmable organisations.