Marc Benioff wrote this week in TIME magazine about “how the rise of new digital Workers will lead to an unlimited age”:

I’ve always believed that business is the greatest platform for change. Today, as we stand at the brink of this new Agentic Era, I’ve never been more confident in the transformative change that’s possible. AI has the potential to elevate every company, fuel economic growth, uplift communities around the globe, and lead to a future of abundance. If trust is our north star as we navigate this new landscape, agents will empower us to make a meaningful impact at an unprecedented scale.

This abundance argument for the application of AI to work and value creation is certainly exciting, and pregnant with possibility. And this potential future of abundance is not just about AI, although AI could be a force multiplier for other technologies as well. Azeem Azhar’s Ten charts to understand the Exponential Age, which he shared recently to mark the 500th edition of Exponential View, is a good indicator of how many factors are coming together to accelerate change:

As I mentioned yesterday, I sent the first edition to 20 friends in 2015 and called it Square 33. This was a nod to the chessboard-rice analogy of exponential growth. The first 32 squares on a chessboard involve relatively modest numbers that don’t feel world-changing. But crossing into the 33rd square launches us into the numbers that seem incomprehensible.

We are in square 33.

Who’s the Agent Now?

Companies are already thinking about not just adding agentic AI into the process landscape of organisations, but going further and faster towards agentic workers performing low-level tasks under their own control. Andy Spence last week wrote about the agentic workforce might develop and how we can get started putting it to work.

But we are only just starting to understand the impact of AI on human jobs, tasks and career paths, and current evidence suggests there is a lot to do if we are to avoid many people being completely left behind by this age of abundance. At the same time, contemporary political shifts seem to be moving away from the idea of social safety nets and employee protection, so this is a potential minefield of societal problems if we don’t get it right.

Rohit Krishnan wrote about this re-alignment recently, and pointed out that questions about the skills, purpose and job impact of AI are complicated and nuanced:

AI reduces the gap between the high and low skilled. If coming up with ideas is your bottleneck, as it seems possible for those who are lower skilled, AI is a boon. If coming up with ideas is where you shine, as a high skilled researcher, well …

This, if you think about it, is similar to the impact of automation work we’ve seen elsewhere. Assembly lines took away the fun parts of craftsmanship regarding building a beautiful finished product. Even before that, machine tools took that away more from the machinist. Algorithmic management of warehouses in Amazon does this.

Although we like to believe that AI and automation will bump people up the value chain by automating repetitive tasks, the devil is in the detail of how we deploy this and how we enable not just organisational readiness, but also people readiness.

Learning as a Key to AI Readiness

HR functions will clearly be impacted in a major way.

Diginomica recently wrote about the HR influencer Josh Bersin, and his views on the ROI of AI for HR and how it will change the function:

We had an example where we were trying to figure out the impact of overtime on profitability. That might be a three month project for an analyst. Well, with AI, it might be three hours or it might be three minutes. So now, we can make decisions faster and operate in a more dynamic way. Companies will pay for that, both in the labor and the time it took. Also when things take a long time, you quite often don’t do them at all. You just don’t do the analysis. You’re just flying blind.

He also foresees a shake-up of the systems that HR rely on to manage their portfolio, as more of this becomes automated or superfluous:

The vendors selling you software today are probably not going to sell you software then. They’re probably going to sell you services. A lot of the things that people are spending a lot of money on in their tech stack are going to be decomposed into services.

Perhaps the key failing of AI readiness is in areas related to learning and re-skilling. Slack’s Workforce Index survey of 17,000+ desk workers around the world found that:

Executives are all in on AI, with 99% planning AI investment in the coming year. Workers, too, are committed to AI with 76% saying they want to become an AI expert. And yet, for the first time since generative AI’s introduction, there are indicators that excitement is cooling among the global workforce as many workers feel confused about how to use AI at work.

This survey found that ‘permission to use’, education and training (PET) are still not keeping pace with developments in the field:

In our last Workforce Index, we saw that those who are trained to use AI are up to 19 times as likely to report that AI is improving their productivity. And yet lack of AI training remains a persistent problem; as of August 2024, just 7% of desk workers consider themselves expert AI users. The majority of desk workers (61%) have spent less than five hours learning how to use AI and 30% of workers say they’ve had no AI training at all, including no self-directed learning or experimentation.

Governments and inter-governmental bodies are also waking up to the broader challenges this lack of readiness will pose, and starting to invest heavily in education. Diginomica covered the Lloyds Bank 2024 UK Consumer Digital Index, and focused on some of its benchmarking results that might point to changes in general skill levels:

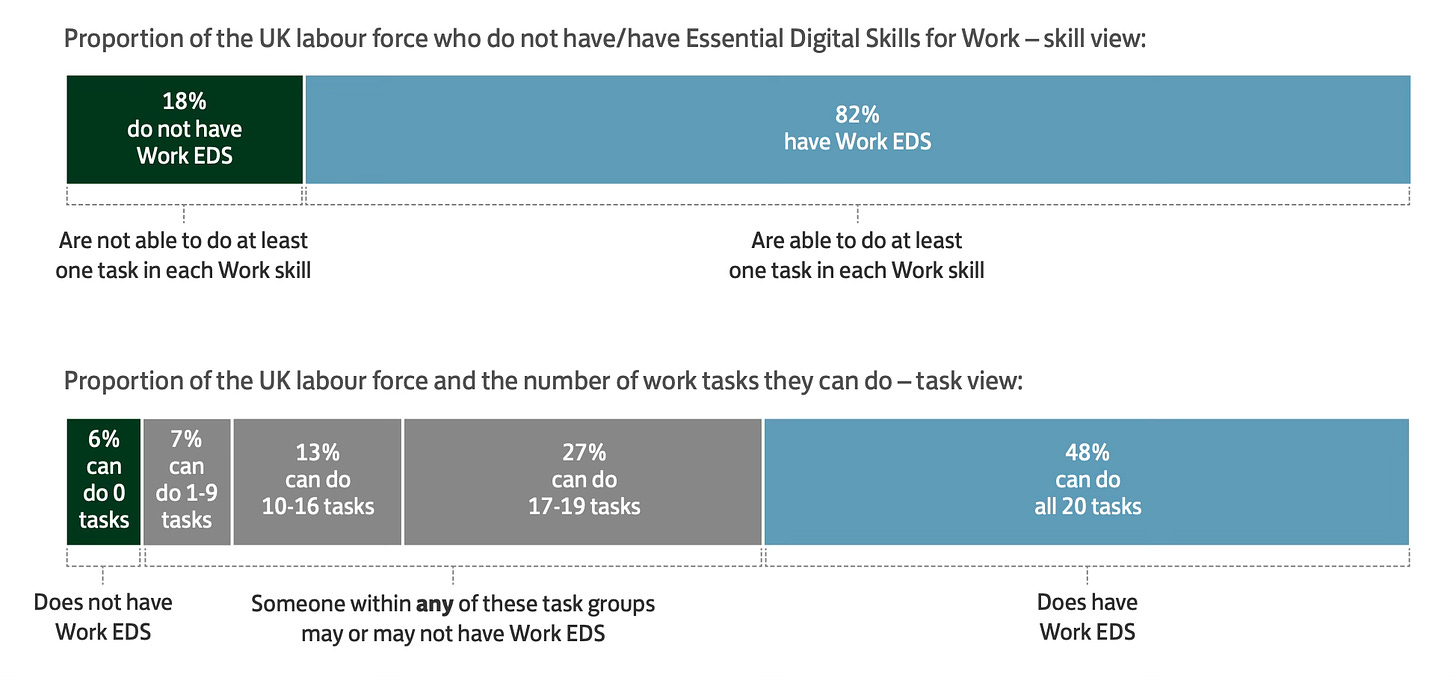

As well as insights into the digital divide on a personal level, the report also explores digital skills in the workplace, through checking how many workers aged 18 and above can complete a selection of up to 20 different tasks. These include using messaging apps, finding information online to solve work-related problems, and controlling privacy and marketing settings for websites and accounts.

While around 33 million (82%) of UK workers have some of the essential digital skills for work, only 19.3 million (48%) can do all 20 tasks. Over two million (six percent) couldn’t complete any of the 20 tasks, while over seven million (18%) could only do between one and nine tasks.

Of note also is the tech sector, where one in five workers can’t do all 20 tasks, an industry where it would be expected to have nearer to 100% skills capability.

Lloyds Bank UK Consumer Digital Index 2024

Transforming and Co-ordinating Key Functions

In a piece called AI transformation is the new digital transformation. Here’s why that change matters, Mark Samuels of ZDNet tries to zoom out and remind us that AI is a key part (and also a driver) of digital transformation, so success will depend as much on change management as it does on implementing exciting new tech features in the workplace.

Related to this, we still have too many functional disconnects on AI readiness and implementation, and the conversation about how this impacts jobs has barely begun:

Gabriela Vogel, a senior director analyst in the Executive Leadership of Digital Business (ELDB) practice at tech analyst Gartner, told ZDNET that her firm’s 2024 CEO Survey suggests many bosses are responding to the hype about Gen AI by demanding AI rather than digital transformations.

“It’s a frustrating position for CIOs, and it’s become a very, very political position for digital leaders because they have a lot of knowledge. So, when do they turn to CEOs and say, ‘No, that’s not what’s happening. That’s not what the technology does,'” she says.

We need better, more connected conversations and coordination about technology adoption at the C-Suite level, as we have argued for some time.

Another related challenge posed by this disconnect is that functions like marketing, HR, finance and operations have all been big buyers of the kind of monolithic platforms that were previously able to work as stand-alone platform, but which now are likely to be replaced, as Josh Bersin noted in relation to HR. Moving forward, we need these functions and their respective CxO roles to think in terms of capability development, and work together to map and integrate those shared capabilities, rather than continue with generic point solutions.

Vasiliy Fomichev, Digital Solutions Head at Zont Digital talked to Diginomica about what he calls the composable CMO and touched on this issue as well:

I think CMOs at their level, they need to understand the capabilities. They need to understand what’s possible and what’s available to be able to make the right decisions in terms of what capabilities to bring. Individually, they don’t necessarily need to be technology savvy, as in really knowing how that works. They need to understand what it can do, and as an orchestrator, bring the right tools at the right time into the space, and it’s IT’s job to make sure that they can do that.

And this is where I think there is such an easy win to be had in terms of AI readiness, as we set out in our post Accelerating the Map → Change → Learn loop to guide enterprise AI adoption: get CxO roles together to map use cases and existing capabilities, components and key services that could be enhanced by AI and automation technologies on a common shared map. Then identify gaps and improvement goals that can go into the development roadmap, and align learning and change efforts around these capability goals, in addition to teaching the basics of AI use, prompting and service-oriented ways of working.

Let’s hope more organisations see the need for ongoing leadership collaboration around AI and don’t just leave it in the hands of CIO functions to deliver magical incantations without the rest of the organisation being ready to use them.

We have developed a simple diagnostic tool to assess AI readiness, and a leadership workshop design to help interpret and plan readiness activities based on its output. If you are interested to learn more, please check our website.