Work Has Changed Forever

Whatever politicians might say about sandwich shop economics and the billions they have injected into the old economy to stave off redundancies (and boost electoral capital), the question of whether working life can ever return to pre-pandemic normality has already been definitively answered by businesses world-wide.

Their assessment, backed by multiple studies (see one of the latest ones here from Cisco, hat-tip Sharon O’Dea), is that working life has changed for good, regardless of when COVID-19 might be brought under control – and that the operational focus should shift on how far, how often, and in what form business plans should encompass remote working for most office workers.

From tech companies like Twitter extending home working “forever”, to manufacturing companies with large physical operations, pragmatic companies are implementing plans to reduce office space, improve connectivity and technology infrastructure, ramp up digital tools training, and implement more flexible working habits to prepare for what is increasingly referred to as the ‘next’ normal – i.e. a world heavily impacted by the current crisis and a workplace that is unlikely to revert to ‘business as usual’ any time soon, if at all, as Vala Afshar from Salesforce argues here.

Cui Bono?

Sadly for many workers, much management coordination activity continues to be focussed on replicating pre-existing processes, methods and rituals, but using digital tools. The result? Burnout.

The default leadership coordination method of meetings and reporting, coupled with an inability to work asynchronously (despite many digital tools to help us do just that), plus limited leisure activity encouraging more time at our home desks, means that some of the time we used to spend resting, travelling, thinking or forming social bonds is now spent working an additional 10 hours each week, on average.

At the same time, the demarcation line between work and personal life – already heavily blurred by always-on connectivity before the pandemic – has become thinner than ever. In addition, given the ease with which digital tools lend themselves to constant communication while simultaneously being a poor substitute for presence,

“We’re spending more time than ever reporting, trying to make our work visible to those around us. This is probably not the best use of our time”,

as Leisa Reichelt of Atlassian recently wrote.

Heading for Shutdown

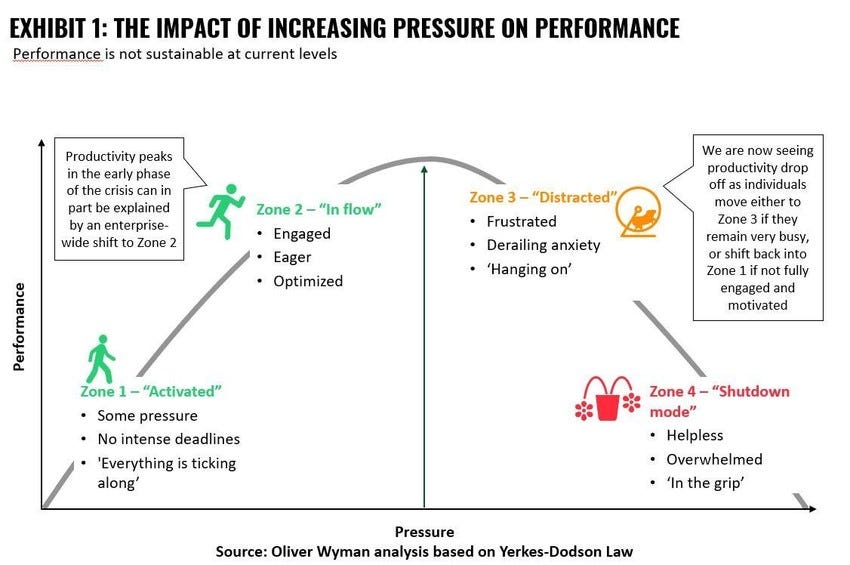

Separately, in this article for the World Economic Forum, Keith McCambridge from Oliver Wyman neatly illustrates the burnout challenge by adapting the century-old Yerkes-Dodson Law regarding the empirical relationship between workplace stress and performance:

“As stress continues, people typically pass through four zones: in the first zone, they are “activated”. Next, they begin to feel “in the flow” and at their peak performance. But if pressure continues to rise, many people enter a third zone of becoming “distracted” before possibly moving into “shutdown mode,” from which they may not return. And that’s just what we are seeing in many organizations now.”

Burnout is a serious issue, which warrants urgent attention. As a workforce planning expert recently told me,

“Little has changed in how we work, but everyone’s working hours have increased – workforce analytics tell us that productivity numbers shot up in March [2020] and have stayed there. This level of activity is not sustainable.”

And yet, leaders also routinely tell us that they have no time to learn how more digital and sustainable ways of working could help them to address these very challenges – which makes me wonder if using just some of the extra 10 hours they now work each week to learn how to better cope and manage in the ‘next’ normal might be part of the solution.

Perhaps that is where executive education and leadership development should focus right now – teaching managers how to exemplify not only digital-first working and asynchronous collaboration rather than Zoom hell, but also a better work-life balance, and demonstrate that remote working does not need ‘presenteeism’ or workload boasting.